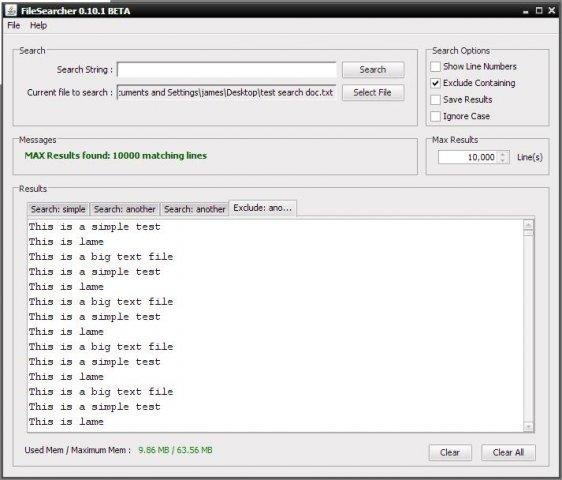

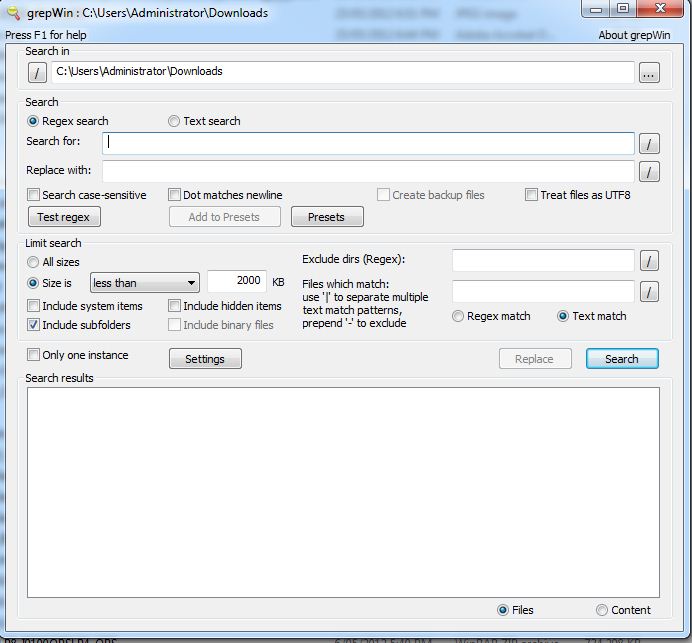

Grep is a basic program used for pattern matching and it was written in the 70s along with the rest of the UNIX tool that we know and love (or hate). Learning grep has a lot more to it than regexes. To get started with it and to see the beauty and elegance of grep you need to see some real-world examples, first. Windows Grep is a tool for searching files for text strings that you specify. Although Windows and many other programs have file searching capabilities built-in, none can match the power. Apr 18, 2018 grepWin is a simple search and replace tool which can use regular expressions to do its job. This allows to do much more powerful searches and replaces. Note: project has moved to GitHub. Another grep tool I now use all the time on Windows is AstroGrep: Its ability to show me more than just the line search (i.e. The -context=NUM of a command-line grep) is invaluable. Very fast, even on an old computer with non- SSD drive (I know, they used to do this hard drive with spinning disks, called platters, crazy right?).

On Unix-like operating systems, the grep command processes text line by line, and prints any lines which match a specified pattern.

This page covers the GNU/Linux version of grep.

Syntax

Overview

Grep, which stands for 'global regular expression print,' is a powerful tool for matching a regular expression against text in a file, multiple files, or a stream of input. It searches for the PATTERN of text you specified on the command line, and outputs the results for you.

Example usage

Let's say want to quickly locate the phrase 'our products' in HTML files on your machine. Let's start by searching a single file. Here, our PATTERN is 'our products' and our FILE is product-listing.html.

A single line was found containing our pattern, and grep outputs the entire matching line to the terminal. The line is longer than our terminal width so the text wraps around to the following lines, but this output corresponds to exactly one line in our FILE.

NoteThe PATTERN is interpreted by grep as a regular expression. In the above example, all the characters we used (letters and a space) are interpreted literally in regular expressions, so only the exact phrase will be matched. Other characters have special meanings, however — some punctuation marks, for example. For more information, see: Regular expression quick reference.

GrepWin - Stefans Tools

Viewing grep output in color

If we use the --color option, our successful matches will be highlighted for us:

Viewing line numbers of successful matches

It will be even more useful if we know where the matching line appears in our file. If we specify the -n option, grep will prefix each matching line with the line number:

Our matching line is prefixed with '18:' which tells us this corresponds to line 18 in our file.

Performing case-insensitive grep searches

What if 'our products' appears at the beginning of a sentence, or appears in all uppercase? We can specify the -i option to perform a case-insensitive match:

Using the -i option, grep finds a match on line 23 as well.

Searching multiple files using a wildcard

If we have multiple files to search, we can search them all using a wildcard in our FILE name. Instead of specifying product-listing.html, we can use an asterisk ('*') and the .html extension. When the command is executed, the shell expands the asterisk to the name of any file it finds (in the current directory) which ends in '.html'.

Notice that each line starts with the specific file where that match occurs.

Recursively searching subdirectories

We can extend our search to subdirectories and any files they contain using the -r option, which tells grep to perform its search recursively. Let's change our FILE name to an asterisk ('*'), so that it matches any file or directory name, and not only HTML files:

This gives us three additional matches. Notice that the directory name is included for any matching files that are not in the current directory.

Using regular expressions to perform more powerful searches

The true power of grep is that it can match regular expressions. (That's what the 're' in 'grep' stands for). Regular expressions use special characters in the PATTERN string to match a wider array of strings. Let's look at a simple example.

Let's say you want to find every occurrence of a phrase similar to 'our products' in your HTML files, but the phrase should always start with 'our' and end with 'products'. We can specify this PATTERN instead: 'our.*products'.

In regular expressions, the period ('.') is interpreted as a single-character wildcard. It means 'any character that appears in this place will match.' The asterisk ('*') means 'the preceding character, appearing zero or more times, will match.' So the combination '.*' will match any number of any character. For instance, 'our amazing products', 'ours, the best-ever products', and even 'ourproducts' will match. And because we're specifying the -i option, 'OUR PRODUCTS' and 'OuRpRoDuCtS will match as well. Let's run the command with this regular expression, and see what additional matches we can get:

Here, we also got a match from the phrase 'our fine products'.

Grep Tool Linux

Grep is a powerful tool to help you work with text files, and it gets even more powerful when you become comfortable using regular expressions.

Technical description

grep searches the named input FILEs (or standard input if no files are named, or if a single dash ('-') is given as the file name) for lines containing a match to the given PATTERN. By default, grep prints the matching lines.

Also, three variant programs egrep, fgrep and rgrep are available:

- egrep is the same as running grep -E. In this mode, grep evaluates your PATTERN string as an extended regular expression (ERE). Nowadays, ERE does not 'extend' very far beyond basic regular expressions, but they can still be very useful. For more information about extended regular expressions, see: Basic vs. extended regular expressions, below.

- fgrep is the same as running grep -F. In this mode, grep evaluates your PATTERN string as a 'fixed string' — every character in your string is treated literally. For example, if your string contains an asterisk ('*'), grep will try to match it with an actual asterisk rather than interpreting this as a wildcard. If your string contains multiple lines (if it contains newlines), each line will be considered a fixed string, and any of them can trigger a match.

- rgrep is the same as running grep -r. In this mode, grep performs its search recursively. If it encounters a directory, it traverses into that directory and continue searching. (Symbolic links are ignored; if you want to search directories that are symbolically linked, use the -R option instead).

In older operating systems, egrep, fgrep and rgrep were distinct programs with their own executables. In modern systems, these special command names are shortcuts to grep with the appropriate flags enabled. They are functionally equivalent.

General options

| --help | Print a help message briefly summarizing command-line options, and exit. |

| -V, --version | Print the version number of grep, and exit. |

Match selection options

| -E, --extended-regexp | Interpret PATTERN as an extended regular expression (see: Basic vs. extended regular expressions). |

| -F, --fixed-strings | Interpret PATTERN as a list of fixed strings, separated by newlines, that is to be matched. |

| -G, --basic-regexp | Interpret PATTERN as a basic regular expression (see: Basic vs. extended regular expressions). This is the default option when running grep. |

| -P, --perl-regexp | Interpret PATTERN as a Perl regular expression. This functionality is still experimental, and may produce warning messages. |

Matching control options

| -ePATTERN, --regexp=PATTERN | Use PATTERN as the pattern to match. This can specify multiple search patterns, or to protect a pattern beginning with a dash (-). |

| -fFILE, --file=FILE | Obtain patterns from FILE, one per line. |

| -i, --ignore-case | Ignore case distinctions in both the PATTERN and the input files. |

| -v, --invert-match | Invert the sense of matching, to select non-matching lines. |

| -w, --word-regexp | Select only those lines containing matches that form whole words. The test is that the matching substring must either be at the beginning of the line, or preceded by a non-word constituent character. Or, it must be either at the end of the line or followed by a non-word constituent character. Word-constituent characters are letters, digits, and underscores. |

| -x, --line-regexp | Select only matches that exactly match the whole line. |

| -y | The same as -i. |

General output control

| -c, --count | Instead of the normal output, print a count of matching lines for each input file. With the -v, --invert-match option (see below), count non-matching lines. |

| --color[=WHEN], --colour[=WHEN] | Surround the matched (non-empty) strings, matching lines, context lines, file names, line numbers, byte offsets, and separators (for fields and groups of context lines) with escape sequences to display them in color on the terminal. The colors are defined by the environment variable GREP_COLORS. The older environment variable GREP_COLOR is still supported, but its setting does not have priority. WHEN is never, always, or auto. |

| -L, --files-without-match | Instead of the normal output, print the name of each input file from which no output would normally be printed. The scanning stops on the first match. |

| -l, --files-with-matches | Instead of the normal output, print the name of each input file from which output would normally be printed. The scanning stops on the first match. |

| -mNUM, --max-count=NUM | Stop reading a file after NUM matching lines. If the input is standard input from a regular file, and NUM matching lines are output, grep ensures that the standard input is positioned after the last matching line before exiting, regardless of the presence of trailing context lines. This enables a calling process to resume a search. When grep stops after NUM matching lines, it outputs any trailing context lines. When the -c or --count option is also used, grep does not output a count greater than NUM. When the -v or --invert-match option is also used, grep stops after outputting NUM non-matching lines. |

| -o, --only-matching | Print only the matched (non-empty) parts of a matching line, with each such part on a separate output line. |

| -q, --quiet, --silent | Quiet; do not write anything to standard output. Exit immediately with zero status if any match is found, even if an error was detected. Also see the -s or --no-messages option. |

| -s, --no-messages | Suppress error messages about nonexistent or unreadable files. |

Output line prefix control

| -b, --byte-offset | Print the 0-based byteoffset in the input file before each line of output. If -o (--only-matching) is specified, print the offset of the matching part itself. |

| -H, --with-filename | Print the file name for each match. This is the default when there is more than one file to search. |

| -h, --no-filename | Suppress the prefixing of file names on output. This is the default when there is only one file (or only standard input) to search. |

| --label=LABEL | Display input actually coming from standard input as input coming from file LABEL. This is especially useful when implementing tools like zgrep, e.g., gzip -cd foo.gz | grep --label=foo -H something. See also the -H option. |

| -n, --line-number | Prefix each line of output with the 1-based line number within its input file. |

| -T, --initial-tab | Make sure that the first character of actual line content lies on a tab stop, so that the alignment of tabs looks normal. This is useful with options that prefix their output to the actual content: -H, -n, and -b. To improve the probability that lines from a single file will all start at the same column, this also causes the line number and byte offset (if present) to be printed in a minimum size field width. |

| -u, --unix-byte-offsets | Report Unix-style byte offsets. This switch causes grep to report byte offsets as if the file were a Unix-style text file, i.e., with CR characters stripped off. This produces results identical to running grep on a Unix machine. This option has no effect unless -b option is also used; it has no effect on platforms other than MS-DOS and MS-Windows. |

| -Z, --null | Output a zero byte (the ASCIINUL character) instead of the character that normally follows a file name. For example, grep -lZ outputs a zero byte after each file name instead of the usual newline. This option makes the output unambiguous, even in the presence of file names containing unusual characters like newlines. This option can be used with commands like find -print0, perl-0, sort-z, and xargs-0 to process arbitrary file names, even those that contain newline characters. |

Context line control

| -ANUM, --after-context=NUM | Print NUM lines of trailing context after matching lines. Places a line containing a group separator (--) between contiguous groups of matches. With the -o or --only-matching option, this has no effect and a warning is given. |

| -BNUM, --before-context=NUM | Print NUM lines of leading context before matching lines. Places a line containing a group separator (--) between contiguous groups of matches. With the -o or --only-matching option, this has no effect and a warning is given. |

| -CNUM, -NUM, --context=NUM | Print NUM lines of output context. Places a line containing a group separator (--) between contiguous groups of matches. With the -o or --only-matching option, this has no effect and a warning is given. |

File and directory selection

| -a, --text | Process a binary file as if it were text; this is equivalent to the --binary-files=text option. |

| --binary-files=TYPE | If the first few bytes of a file indicate that the file contains binary data, assume that the file is of type TYPE. By default, TYPE is binary, and grep normally outputs either a one-line message saying that a binary file matches, or no message if there is no match. If TYPE is without-match, grep assumes that a binary file does not match; this is equivalent to the -I option. If TYPE is text, grep processes a binary file as if it were text; this is equivalent to the -a option. Warning: grep --binary-files=text might output binary garbage, which can have nasty side effects if the output is a terminal and if the terminal driver interprets some of it as commands. |

| -DACTION, --devices=ACTION | If an input file is a device, FIFO or socket, use ACTION to process it. By default, ACTION is read, which means that devices are read as if they were ordinary files. If ACTION is skip, devices are silently skipped. |

| -dACTION, --directories=ACTION | If an input file is a directory, use ACTION to process it. By default, ACTION is read, i.e., read directories as if they were ordinary files. If ACTION is skip, silently skip directories. If ACTION is recurse, read all files under each directory, recursively, following symbolic links only if they are on the command line. This is equivalent to the -r option. |

| --exclude=GLOB | Skip files whose base name matches GLOB (using wildcard matching). A file-name glob can use *, ?, and [...] as wildcards, and to quote a wildcard or backslash character literally. |

| --exclude-from=FILE | Skip files whose base name matches any of the file-name globs read from FILE (using wildcard matching as described under --exclude). |

| --exclude-dir=DIR | Exclude directories matching the pattern DIR from recursive searches. |

| -I | Process a binary file as if it did not contain matching data; this is equivalent to the --binary-files=without-match option. |

| --include=GLOB | Search only files whose base name matches GLOB (using wildcard matching as described under --exclude). |

| -r, --recursive | Read all files under each directory, recursively, following symbolic links only if they are on the command line. This is equivalent to the -d recurse option. |

| -R, --dereference-recursive | Read all files under each directory, recursively. Follow all symbolic links, unlike -r. |

Other options

| --line-buffered | Use line buffering on output. This can cause a performance penalty. |

| --mmap | If possible, use the mmap system call to read input, instead of the default read system call. In some situations, --mmap yields better performance. However, --mmap can cause undefined behavior (including core dumps) if an input file shrinks while grep is operating, or if an I/O error occurs. |

| -U, --binary | Treat the file(s) as binary. By default, under MS-DOS and MS-Windows, grep guesses the file type by looking at the contents of the first 32 KB read from the file. If grep decides the file is a text file, it strips the CR characters from the original file contents (to make regular expressions with ^ and $ work correctly). Specifying -U overrules this guesswork, causing all files to be read and passed to the matching mechanism verbatim; if the file is a text file with CR/LF pairs at the end of each line, this causes some regular expressions to fail. This option has no effect on platforms other than MS-DOS and MS-Windows. |

| -z, --null-data | Treat the input as a set of lines, each terminated by a zero byte (the ASCII NUL character) instead of a newline. Like the -Z or --null option, this option can be used with commands like sort-z to process arbitrary file names. |

Regular expressions

A regular expression is a pattern that describes a set of strings. Regular expressions are constructed analogously to arithmetic expressions, using various operators to combine smaller expressions.

grep understands three different versions of regular expression syntax: 'basic' (BRE), 'extended' (ERE) and 'perl' (PRCE). In GNUgrep, there is no difference in available functionality between basic and extended syntaxes. In other implementations, basic regular expressions are less powerful. The following description applies to extended regular expressions; differences for basic regular expressions are summarized afterwards. Perl regular expressions give additional functionality.

The fundamental building blocks are the regular expressions that match a single character. Most characters, including all letters and digits, are regular expressions that match themselves. Any metacharacter with special meaning may be quoted by preceding it with a backslash.

The period (.) matches any single character.

Character classes and bracket expressions

A bracket expression is a list of characters enclosed by [ and ]. It matches any single character in that list; if the first character of the list is the caret ^ then it matches any character not in the list. For example, the regular expression [0123456789] matches any single digit.

Within a bracket expression, a range expression consists of two characters separated by a hyphen. It matches any single character that sorts between the two characters, inclusive, using the locale's collating sequence and character set. For example, in the default C locale, [a-d] is equivalent to [abcd]. Many locales sort characters in dictionary order, and in these locales [a-d] is often not equivalent to [abcd]; it might be equivalent to [aBbCcDd], for example. To obtain the traditional interpretation of bracket expressions, you can use the C locale by setting the LC_ALL environment variable to the value C.

Finally, certain named classes of characters are predefined within bracket expressions, as follows. Their names are self explanatory, and they are [:alnum:], [:alpha:], [:cntrl:], [:digit:], [:graph:], [:lower:], [:print:], [:punct:], [:space:], [:upper:], and [:xdigit:]. For example, [[:alnum:]] means the character class of numbers and letters in the current locale. In the C locale and ASCII character set encoding, this is the same as [0-9A-Za-z]. (Note that the brackets in these class names are part of the symbolic names, and must be included in addition to the brackets delimiting the bracket expression.) Most metacharacters lose their special meaning inside bracket expressions. To include a literal ] place it first in the list. Similarly, to include a literal ^ place it anywhere but first. Finally, to include a literal -, place it last.

Anchoring

The caret ^ and the dollar sign $ are metacharacters that respectively match the empty string at the beginning and end of a line.

The backslash character and special expressions

The symbols < and > respectively match the empty string at the beginning and end of a word. The symbol b matches the empty string at the edge of a word, and B matches the empty string provided it's not at the edge of a word. The symbol w is a synonym for [_[:alnum:]] and W is a synonym for [^_[:alnum:]].

Repetition

A regular expression may be followed by one of several repetition operators:

| ? | The preceding item is optional and matched at most once. |

| * | The preceding item will be matched zero or more times. |

| + | The preceding item will be matched one or more times. |

| {n} | The preceding item is matched exactly n times. |

| {n,} | The preceding item is matched n or more times. |

| {n,m} | The preceding item is matched at least n times, but not more than m times. |

Concatenation

Two regular expressions may be concatenated; the resulting regular expression matches any string formed by concatenating two substrings that respectively match the concatenated expressions.

Alternation

Two regular expressions may be joined by the infix operator |; the resulting regular expression matches any string matching either alternate expression.

Precedence

Repetition takes precedence over concatenation, which in turn takes precedence over alternation. A whole expression may be enclosed in parentheses to override these precedence rules and form a subexpression.

Back references and subexpressions

The back-reference n, where n is a single digit, matches the substring previously matched by the nth parenthesized subexpression of the regular expression.

Basic vs. extended regular expressions

In basic regular expressions the metacharacters ?, +, {, |, (, and ) lose their special meaning; instead use the backslashed versions ?, +, {, |, (, and ).

Traditional versions of egrep did not support the { metacharacter, and some egrep implementations support { instead, so portable scripts should avoid { in grep -E patterns and should use [{] to match a literal {.

GNU grep -E attempts to support traditional usage by assuming that { is not special if it would be the start of an invalid interval specification. For example, the command grep -E '{1' searches for the two-character string {1 instead of reporting a syntax error in the regular expression. POSIX allows this behavior as an extension, but portable scripts should avoid it.

Environment variables

The behavior of grep is affected by the following environment variables.

The locale for category LC_foo is specified by examining the three environment variables LC_ALL, LC_foo, and LANG, in that order. The first of these variables that is set specifies the locale. For example, if LC_ALL is not set, but LC_MESSAGES is set to pt_BR, then the Brazilian Portuguese locale is used for the LC_MESSAGES category. The C locale is used if none of these environment variables are set, if the locale catalog is not installed, or if grep was not compiled with national language support (NLS).

Other variables of note:

| GREP_OPTIONS | This variable specifies default options to be placed in front of any explicit options. For example, if GREP_OPTIONS is '--binary- files=without-match --directories=skip', grep behaves as if the two options --binary-files=without-match and --directories=skip had been specified before any explicit options. Option specifications are separated by whitespace. A backslash escapes the next character, so it can specify an option containing whitespace or a backslash. | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| GREP_COLOR | This variable specifies the color used to highlight matched (non-empty) text. It is deprecated in favor of GREP_COLORS, but still supported. The mt, ms, and mc capabilities of GREP_COLORS have priority over it. It can only specify the color used to highlight the matching non-empty text in any matching line (a selected line when the -v command-line option is omitted, or a context line when -v is specified). The default is 01;31, which means a bold red foreground text on the terminal's default background. | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| GREP_COLORS | Specifies the colors and other attributes used to highlight various parts of the output. Its value is a colon-separated list of capabilities that defaults to ms=01;31:mc=01;31:sl=:cx=:fn=35:ln=32:bn=32:se=36 with the rv and ne boolean capabilities omitted (i.e., false). Supported capabilities are as follows:

Note that boolean capabilities have no =... part. They are omitted (i.e., false) by default and become true when specified. See the Select Graphic Rendition (SGR) section in the documentation of the text terminal that is used for permitted values and their meaning as character attributes. These substring values are integers in decimal representation and can be concatenated with semicolons. grep takes care of assembling the result into a complete SGR sequence (33[...m). Common values to concatenate include 1 for bold, 4 for underline, 5 for blink, 7 for inverse, 39 for default foreground color, 30 to 37 for foreground colors, 90 to 97 for 16-color mode foreground colors, 38;5;0 to 38;5;255 for 88-color and 256-color modes foreground colors, 49 for default background color, 40 to 47 for background colors, 100 to 107 for 16-color mode background colors, and 48;5;0 to 48;5;255 for 88-color and 256-color modes background colors. | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| LC_ALL, LC_COLLATE, LANG | These variables specify the locale for the LC_COLLATE category, which determines the collating sequence used to interpret range expressions like [a-z]. | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| LC_ALL, LC_CTYPE, LANG | These variables specify the locale for the LC_CTYPE category, which determines the type of characters, e.g., which characters are whitespace. | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| LC_ALL, LC_MESSAGES, LANG | These variables specify the locale for the LC_MESSAGES category, which determines the language that grep uses for messages. The default C locale uses American English messages. | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| POSIXLY_CORRECT | If set, grep behaves as POSIX requires; otherwise, grep behaves more like other GNU programs. POSIX requires that options that follow file names must be treated as file names; by default, such options are permuted to the front of the operand list and are treated as options. Also, POSIX requires that unrecognized options be diagnosed as 'illegal', but since they are not really against the law the default is to diagnose them as 'invalid'. POSIXLY_CORRECT also disables _N_GNU_nonoption_argv_flags_, described below. | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| _N_GNU_nonoption_argv_flags_ | (Here N is grep's numeric process ID). If the ith character of this environment variable's value is 1, do not consider the ith operand of grep to be an option, even if it appears to be one. A shell can put this variable in the environment for each command it runs, specifying which operands are the results of file name wildcard expansion and therefore should not be treated as options. This behavior is available only with the GNU C library, and only when POSIXLY_CORRECT is not set. |

Exit status

The exit status is 0 if selected lines are found, and 1 if not found. If an error occurred the exit status is 2.

Examples

TipIf you haven't already seen our example usage section, we suggest reviewing that section first.

Search /etc/passwd for user chope.

Search the Apache error_log file for any error entries that happened on May 31st at 3 A.M. By adding quotes around the string, this allows you to place spaces in the grep search.

Recursively search the directory /www/, and all subdirectories, for any lines of any files which contain the string 'computerhope'.

Search the file myfile.txt for lines containing the word 'hope'. Only lines containing the distinct word 'hope' are matched. Lines where 'hope' is part of a word (e.g., 'hopes') are not be matched.

Same as previous command, but displays a count of how many lines were matched, rather than the matching lines themselves.

Inverse of previous command: displays a count of the lines in myfile.txt which do not contain the word 'hope'.

Display the file names (but not the matching lines themselves) of any files in /www/ (but not its subdirectories) whose contents include the string 'hope'.

Related commands

ed — A simple text editor.

egrep — Filter text which matches an extended regular expression.

sed — A utility for filtering and transforming text.

sh — The Bourne shell command interpreter.

Windows Grep is a free search tool for Windows that allows you search the text of multiple files at the same time.

Its interface, although simple, is very practical and, thanks to its assistant, it is really easy to perform searches.

You can make various adjustments to ensure you find the file that you want, such as the use of regular expressions or identical terms, the ability to search multiple directories, or eliminate files by extension, among other options.

All this makes Windows Grep a utility that is really worth trying.